By Lucinda Minton Langworthy and Angela R. Morrison

Earlier this year, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reduced the level of the primary annual National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) for fine particulate matter (PM2.5), commonly referred to as soot, from 12-9 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m3), reflecting a 25 percent reduction in the standard intended to be protective of human health. This new NAAQS, which applies outside the fence lines of industrial facilities, is expected to have significant detrimental consequences for American industry due to challenging and costly compliance requirements and for the American economy in general due to higher prices for construction and consumer goods, plus increased imports needed to offset reduced domestic production.

Upon the rule’s release, Portland Cement Association President and CEO Mike Ireland noted, “This new rule strikes at the heart of the U.S. cement industry’s ability to deliver on the Biden Administration’s infrastructure goals, as it would lead to fewer hours of operation at plants, which would mean layoffs, as well as less American cement and concrete at a time when the country needs more.”

The rule becomes effective on May 6, 2024, and immediately any applicant for a Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) air construction permit for a new or modified major stationary source will have to demonstrate that the permitted action’s air emissions will not cause or contribute to a violation of the new standard. This requirement applies even if the PSD permit application was complete before the effective date of the new standard. Cement manufacturing facilities often qualify as “major sources” under this program and may be subject to PSD permitting requirements for new projects. Although a well-controlled new or modernized facility may not in fact lead to a NAAQS violation, it may be impossible to demonstrate this because EPA requires use of conservative computer modeling in combination with overstating background pollution levels and requiring unrealistic assumptions that sources will operate continuously at their maximum allowable emission rate. If the demonstration cannot be made, proposed projects will not be allowed to proceed, potentially impeding job growth and the modernization and expansion of manufacturing and industrial facilities throughout the country.

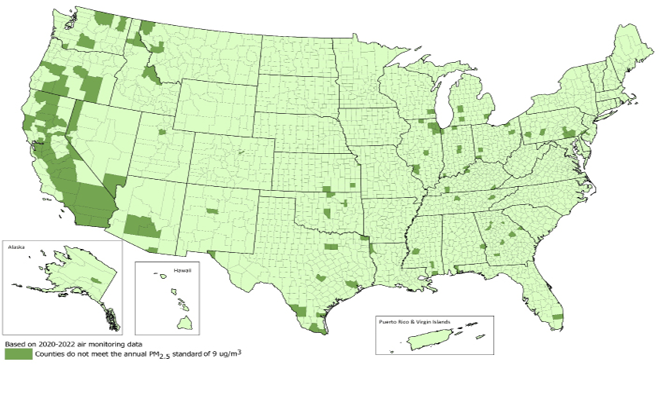

Looking forward, if a monitor measuring ambient air concentrations of PM2.5 reflects an annual average concentration exceeding the new standard, the entire county where the monitor is located will be at risk of a “nonattainment” designation—meaning that sources of PM2.5 located in that county will be subject to additional regulation aimed at reducing emissions and improving air quality. Although EPA does not anticipate designating geographic-based nonattainment areas for the new NAAQS until February 2026, the Agency has initially estimated that the number of counties monitoring violations of the new annual standard will be approximately 120, which is double the number with monitored concentrations above with the current standard. The number is likely to increase because EPA will designate a county as nonattainment for PM2.5 if emissions originating there contribute to a violation of the standard in another county, even if the contributing county’s air quality meets the standard, and contributing counties are not reflected in the current estimate.

Within a year after the nonattainment designations, activities implemented by federal agencies and federally supported highway and transit projects (including locally funded ones) planned in nonattainment and attainment areas will be limited and may not proceed if the associated emissions would cause or contribute to a new violation of the standard, increase the frequency or severity of an existing violation, or delay timely attainment of the standard. This can have an obvious impact on industries that provide materials to construct these projects. At the same time, any increases in PM2.5 from new or modified industrial sources would be allowed only if the most stringent emission controls are utilized and if offsetting reductions are available, meaning that for every new ton of emissions or PM2.5 or a PM2.5 precursor (sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds, and, in some cases, ammonia), there must be at least one ton of permanent emission reductions from another source in the area. The availability of offsets can be difficult to track, and growth in these areas becomes severely limited which negatively affects an area’s economic opportunities and vitality. Unfortunately, the cement industry estimates that approximately one-third of its manufacturing plants are located in areas at risk of being designated nonattainment.

Later, within 18 months after designation, states with nonattainment areas must submit State Implementation Plans (SIPs) to EPA that require existing sources of PM2.5 (or its precursors) to implement or install reasonably available control measures and technology and to meet enforceable emission limitations. The state’s plan must demonstrate that these measures and the resulting reductions in emissions will lead to attainment of the annual 9 µg/m3 standard for PM2.5 within six years after the designation. An area that cannot attain by this deadline will face more stringent control requirements in exchange for more time to attain the standard.

Most atmospheric PM2.5 comes from fugitive sources such as prescribed burning and wildfires and dust from unpaved roads and bare agricultural land, as well as low-volume and wide-spread contributors like commercial cooking, restaurants, wood stoves, and residential fireplaces. The focus of controls to bring areas into attainment, however, will likely continue to be on industrial sources, including cement manufacturing facilities as well as aggregate, block, and ready-mix concrete plants, despite the fact that many are already well-controlled and further control appears difficult and costly if possible at all. EPA has not identified how all of the necessary reductions could be achieved and this becomes the primary responsibility of states. Working with the state air agency as it develops the SIP will provide an opportunity for owners and operators of industrial sources to propose reasonable control options, perhaps even options that would ensure and incentivize emission reductions from certain types of fugitive or area sources.

Even with such industry involvement, as Steel Manufacturers Association President Phillip K. Bell cautions: “[The new NAAQS] threatens successful implementation of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPs and Science Act and the important clean energy provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act [and] will stifle the capital investment that creates jobs, reduces carbon emissions and modernizes manufacturing.”

In short, industry anticipates that the new lower PM2.5 standard will cause the cost of construction materials produced in the United States to increase while at the same time limit increased production of these materials. The effect will be to impede construction projects and economic growth, and thus encourage foreign competition. To help minimize economic impacts for individual facilities and the industry, owners and operators must take an active role in the development of a state’s plan to reduce emissions of PM2.5 and its precursors.

WIDESPREAD COMPLIANCE

Counties with 2020-2022 PM2.5 monitoring data reflecting nonattainment with new NAAQS

Lucinda Minton Langworthy is Counsel and Angela R. Morrison is Senior Attorney with the law firm Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected], respectively.