To address greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with diesel fuel consumption, Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers have devised a new way of powering trucks that could curb pollution, increase efficiency, and reduce or even eliminate their net GHG factor. The concept involves using a plug-in hybrid engine system where the truck is primarily powered by batteries, but with a spark ignition engine versus compression ignition typical of diesel power. That power source would allow trucks to travel the same distances as today’s conventional diesel-powered models, would operate in flex-fuel mode on pure gasoline or alcohol, or blends of the fuels.

|

|

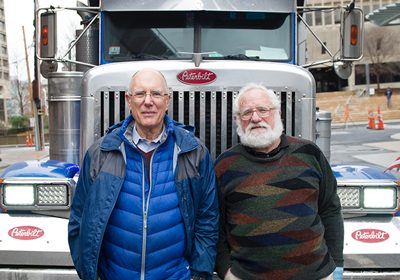

| Leading into the SAE presentation, Daniel Cohn (left) and Leslie Bromberg assessed the potential of spark ignition power for heavy-duty trucks in the MIT Energy Initiative’s Energy Futures quarterly. PHOTO: Stuart Darsch, MIT News Service Office |

While the ultimate goal would be to power trucks entirely with batteries, the researchers note, the flex-fuel hybrid option could provide a way for such trucks to gain early entry into the marketplace by overcoming concerns about limited range, cost, or the need for excessive battery weight to achieve longer range. The new concept was developed by MIT Energy Initiative and Plasma Fusion and Science Center research scientist Daniel Cohn and principal research engineer Leslie Bromberg. They presented the flex-fuel hybrid last month at the annual SAE International conference, and have conducted their work under an Arthur Samberg Energy Innovation Fund grant.

“We’ve been working for a number of years on ways to make engines for cars and trucks cleaner and more efficient, and we’ve been particularly interested in what you can do with spark ignition because it’s intrinsically much cleaner [than compression ignition],” says Cohn.

Compared to a diesel engine vehicle, a gasoline-powered vehicle produces only a tenth as much nitrogen oxide (NOx), a major component of air pollution. In addition, by using a flex-fuel configuration that allows it to run on gasoline, ethanol, methanol, or blends of these, such engines have the potential to emit far less GHG than pure gasoline engines do, and the incremental cost for the fuel flexibility is very small, Cohn and Bromberg observe. If run on pure methanol or ethanol derived from renewable sources such as agricultural waste or municipal trash, the net GHG emissions could even be zero.

“It’s a way of making use of a low-greenhouse-gas fuel” when it’s available, “but always having the option of running it with gasoline” to ensure maximum flexibility, Cohn explains. While Tesla Motors has announced it will be producing an all-electric heavy-duty truck, he adds, “we think that’s going to be very challenging because of the cost and weight of the batteries” needed to provide sufficient range. To meet the expected driving range of conventional diesel trucks, he and Bromberg estimate, would require somewhere between 10 and 15 tons of batteries—a significant fraction of the payload such a vehicle could otherwise carry.

To get around that, Cohn notes, “We think that the way to enable the use of electricity in these vehicles is with a plug-in hybrid.” The proposed engine for such a hybrid is a version of one the two researchers have been working on for years: A highly efficient, flexible-fuel gasoline engine that would weigh far less, be more fuel-efficient, and produce a tenth as much air pollution as the best of today’s diesel-powered vehicles.

Cohn and Bromberg did a detailed analysis of both the engineering and economics of what would be needed to develop such an engine to meet the needs of existing truck operators. In order to match the efficiency of diesels, a mix of alcohol with the gasoline, or even pure alcohol, can be used, and this can be processed using renewable energy sources, they found. Detailed computer modeling of a whole range of desired engine characteristics, combined with screening of the results using an artificial intelligence system, yielded clear indications of the most promising pathways and showed that such substitutions are indeed practically and financially feasible.

In both the present diesel and the proposed flex-fuel vehicles, the emissions are measured at the tailpipe, after a variety of emissions-control systems have done their work in both cases, so the comparison is a realistic measure of real-world emissions. The combination of a hybrid drive and flex-fuel engine is “a way to enable the introduction of electric drive into the heavy truck sector, by making it possible to meet range and cost requirements, and doing it in a way that’s clean,” says Cohn.

The cost advantages that led to the near-universal adoption of diesels for heavy trucking no longer prevail, adds Bromberg. “Over time, gas engines have become more and more efficient, and they have an inherent advantage in producing less air pollution,” she says. And by using the engine in a hybrid system, it can always operate at its optimum speed, maximizing its efficiency.

Methane is an extremely potent GHG, but can be captured and converted to methanol through a simple chemical process. “That’s one of the most attractive ways to make a clean fuel,” notes Bromberg. “I think the alcohol fuels overall have a lot of promise.”

Already, she points out, California has plans for new regulations on truck emissions that are very difficult to meet with diesel engine vehicles. “We think there’s a significant rationale for trucking companies to go to gasoline or flexible fuel,” Cohn says. “The engines and exhaust treatment systems are cheaper, and it’s a way to ensure that they can meet the expected regulations. And combining that with electric propulsion in a hybrid system, given an ever cleaner electric grid, can further reduce emissions and pollution from the trucking sector.”

Pure electric propulsion for trucks is the ultimate goal, but today’s batteries don’t make that a realistic option yet. “Batteries are great, but let’s be realistic about what they can provide,” Cohn affirms.

“We don’t know which is going to be stronger, the desire to reduce greenhouse gases, or the desire to reduce air pollution,” he adds. In the U.S., climate change may be the bigger push, while in India and China air pollution may be more urgent, but the plug-in electric hybrid concept appears to hold value for both conditions.

David Chandler is a member of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology News Office staff.